It’s been a while since we’ve posted here. We’ve been hard at work and busy with life but our shiny new website is a great excuse to write again. In this post, I’ll talk about one of the most interesting features in The Long Road: dynamic storytelling.

In The Long Road, we use dynamic storytelling to control the content that the player sees. As you wander through an unforgiving post-apocalyptic world, your moral compass is tested. Will you give your last scraps of food to a starved group of travellers? Will you risk freeing someone from a trap, knowing that the trappers could be nearby? Will you take shelter with cannibals if it means that you don’t starve?

As you make these choices, you affect the world around you and the content that you see. In the rest of this post, I’ll explain what I mean by dynamic storytelling and how we do use it in The Long Road.

What is dynamic storytelling?

Dynamic storytelling lets the listener (or the player of your game) control how the story is told. This isn’t a new idea: text-adventure games have been around for decades and are, in my eyes, the quintessential example of this. In text-adventure games, the player makes choices that control which parts of the story they see.

However, dynamic storytelling can take on different forms. In Mass Effect 3, the choices you make affect your morality that in turn changes how you experience the game. In Dragon Age Origins you maintain different relationship scores with your party members that affect your conversations with them and even what they do. In TellTale Games' The Wolf Among Us, the choices that you make can drastically alter the story that you experience. Many more games employ similar non-linear approaches to storytelling.

Branching stories

But this is hard to get right. For games that enumerate content for all of the player choices, dynamic storytelling typically requires branching that leads to an exponential explosion in content. To control this, it is often necessary to merge branches or kill off branches altogether. But this is unsatisfying for players, who then feel as though their decisions have little or no impact on the story at all.

A solution: Storylets

There is a nice approach to dynamic storytelling which offers a promising solution: storylets. A storylet is a piece of content that has some prerequisites that determine when it is shown to the player and some effects on the world when it is completed. Storylets are a great way to break up your narrative content to achieve dynamic storytelling.

Emily Short’s wonderful blog post on storylets gives some great examples of how classic story branching structures can be represented as storylets. For the examples above, morality in Mass Effect 3 could be a prerequisite on pieces of narrative content. Certain storylets might only be triggered when morality is above or below a certain threshold. Similarly, in Dragon Age Origins, the relationship score between party members would act as a prerequisite for certain pieces of dialogue.

Classical branching structures can also be represented, by having storylets be prerequisites for other storylets. And of course, you could take various combinations of these approaches.

Dynamic storytelling in The Long Road

We adopt a storylet approach to dynamic storytelling in The Long Road. Armed with Emily Short’s definition, a storylet consists of three things:

- A piece of content

- Some prerequisites for showing that content

- Some effects on the world on completion

Let’s see what each of these corresponds to in The Long Road.

Storylet content

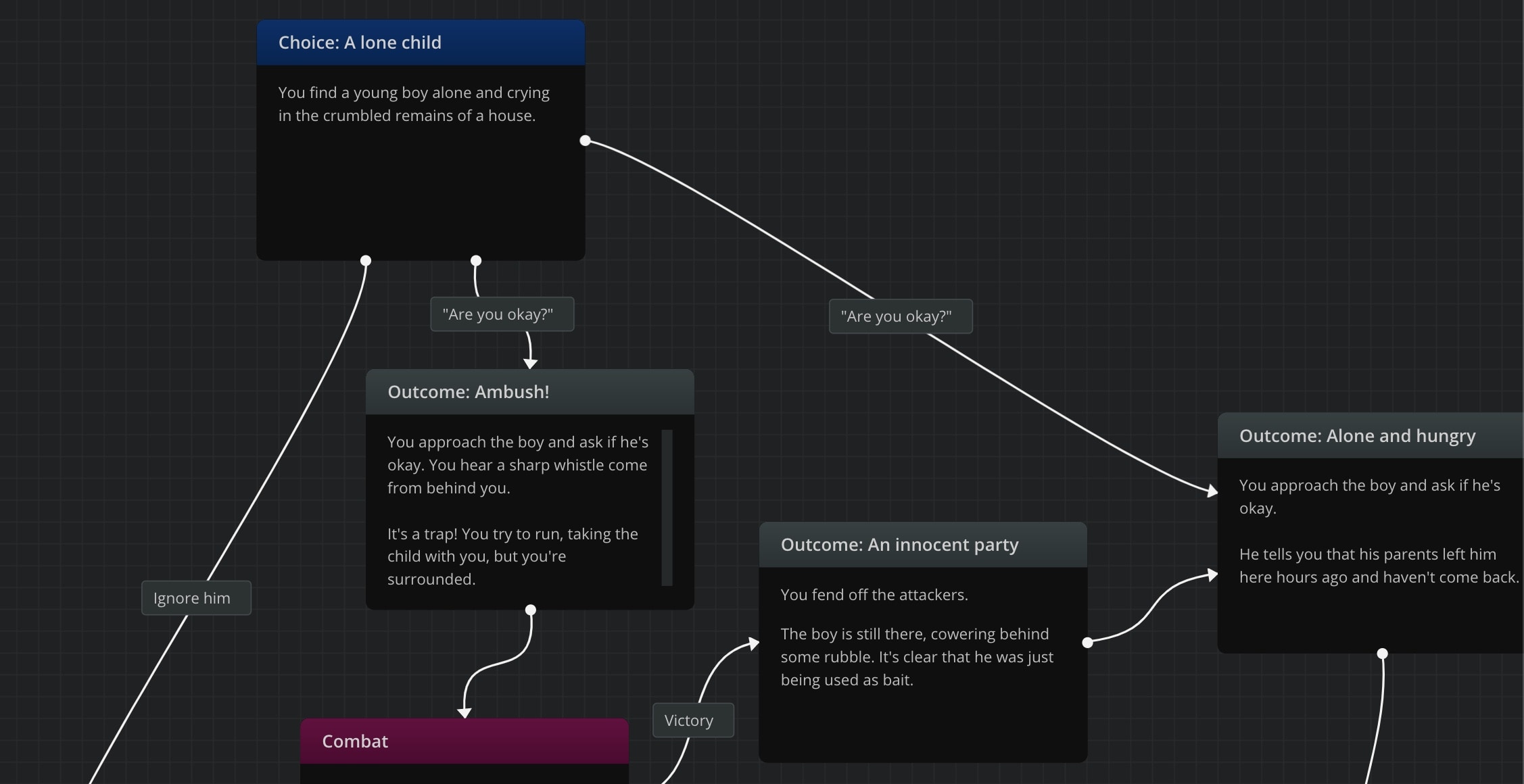

The content of each storylet is itself an interactive branching story. It can be represented as a tree (as in, the data structure). The nodes in the tree represent different stages in the storylet and can be any one of:

- A choice is given as a text description of an event and some text-based options. Example: There’s a cabin standing alone in the forest. A flickering orange light reveals a single window. <Run>, <Investigate>, <Shout a Warning>

- An outcome is given as a text description. It may also include changes in resources, equipment, damage, etc. Example: You loot the corpse, but you’re not the first… You don’t find anything of note.

- Turn-based combat.

- A new party member joining your group.

The edges connect stages depending on the player’s actions. For example which choice they made, whether they succeeded in combat or fled, and whether they accepted the new party member.

A single storylet created using arcweave.

So already each storylet can contain a great deal of variety and requires some effort to produce. We alleviate this effort by keeping each of the storylets fairly short. At the moment, our longest storylets are 6 or so levels deep with the average length being 3-4 levels. We combine this with randomized edge traversal (the same action from the player may lead to different nodes) to add even more variety.

Storylet prerequisites

Different prerequisites may be required to activate a storylet:

- Location

- Each storylet is assigned a location in the world and is activated only when the player is there

- The locations are assigned randomly, but each storylet specifies a biome type where it can spawn

- Progress

- There are progress tiers. Completing storylets increases progress (and difficulty)

- Items

- You must possess, for example, a map, a key, a hand-radio, etc.

- Character

- Some storylets are only available when a certain character is in your party

Notably, some storylets can only be activated once by the player. But other storylets are repeatable events that can be triggered repeatedly in different locations. For example, bandit ambushes, traders, environmental hazards, etc.

This is the set of prerequisites that we currently have in the game. But the system we have implemented is very easy to extend to include other prerequisites, like a morality/reputation system. We’re holding off on these for now until we have a better idea of how much content we’d need with this additional fragmenting.

Effects on the world

Using just the three prerequisites above we have a dynamic world where new storylets are introduced as the player explores and acts. By completing storylets with certain outcomes we spawn new storylets, giving a dynamic quest system. This means that the story that the player experiences depends entirely on the choices they make as they play. Even down to whether they flee a combat encounter or accept a new character into their party.

\

\

Storylets also have an effect on the world state in other meaningful ways. The player might need to pay resource costs to use certain actions (like feeding a starving dog). They might gain new party members (like the dog they kindly fed), or lose party members in combat.

Conclusion

Dynamic storytelling is the feature that we’re most excited about in The Long Road. It makes the world feel dynamic and alive, and the player’s choices feel impactful.

We used the framework of storylets to describe this system, which is a great way to break down a fairly complex piece of the game’s tech. Our technical implementation (and design) has gone through several iterations and we’re really happy with it right now. We’ve planned for modding from the beginning as we love the idea of introducing storylets created by the community.

One of the major challenges of developing content for dynamic storytelling is the sheer volume of content required to enable the player to craft their journey. We break down our content into small bite-sized chunks that we can connect in a more controlled way that resists this exponential explosion in content. The Long Road is a roguelite game, meaning we expect players to play through the game multiple times and experience different parts of the story — randomness plays an important role there too.

We’re excited by what dynamic storytelling brings to the game and can’t wait to see this content filled out as we work towards release!